Counselling for Relationships & Attachment

What is Attachment?

During couples counselling at enduringmind, (whitton) you will learn about how your attachment style can have an impact on the dynamics and patterns of interaction you have in relationships. Each person in the couple brings these patterns of attachment with them from the relationships they formed as a child. Attachment arises out of our first bonding experiences with our parents. It is a special emotional relationship that involves an exchange of comfort, care, survival needs and the physical pleasure of intimacy. Our relationships with attachment figures in adulthood are a reflection of our entire history of developmental relationships with our caregivers & parents in childhood. Research on attachment began with mary ainsworth and john bowlby who described attachment as a "lasting psychological connectedness between human beings" (1960). Bowlby believed that early childhood experiences of bonding have a lasting influence on our patterns of relationship and behaviour in later life. He believed ‘the propensity to make strong emotional bonds to particular individuals is a basic component of human nature’ (1965). Attachment had an evolutionary function because the child’s survival was dependent on the caregiver's love, nurture and protection before it could fend for itself.

Characteristics of attachment styles: ainsworth discovered 4 distinctive characteristics of attachment which enabled human beings to serve their needs as infants and adults:

- Secure base– where the caregiver acts as a base of security from which the child can explore the world and learn to experiment with the transition from dependence to independence.

- Safe haven– the desire to return to the caregiver for comfort and safety in the face of a fear or threat.

- Separation distress– the physical and psychological anxiety which is provoked in the child by the absence of the attachment figure.

- Proximity maintenance- the desire for close proximity to attachment figures for affection & intimacy.

When children are raised with security and confidence by their primary caregivers, who are emotionally available to them, they are less likely to experience separation anxiety than those children raised without secure and consistent care giving. an infant’s confidence in relationships is created or disrupted during a critical window of development and this depends on the caregiver’s emotional availability, attunement and regulation of their children. And it is this which needs to be consistent, stable and secure. if the physical, emotional and social needs of the child are not met by their parents this can lead to a lack of trust and confidence. As a result, anxious attachment styles are triggered in children who fear inconsistent, disruptive and chaotic parenting. And it is more likely that anxious attachments develop in adulthood – with a fear of intimacy, distrust of others, jealousy, as well as swinging between idealising or devaluing partners. Alternatively, if children learn to expect caregivers who are responsive to their needs then they are more trusting and confident in their relationships with others - feeling comfortable with intimacy, secure in relationships and independent.

Four Types of Attachment Style:

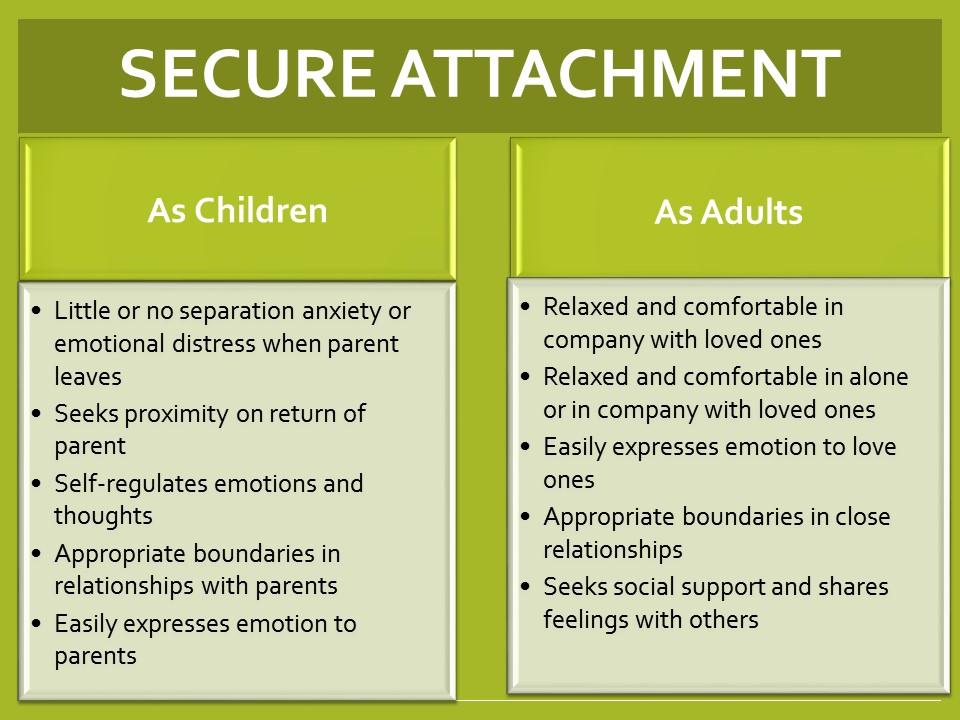

Secure Attachment – children who are securely attached may become visibly upset when their caregivers leave, but are often quickly consoled when their parents return. When frightened, these children seek comfort and proximity to the parent or caregiver. For these children, emotional contact initiated by a parent is warmly accepted and they greet the return of a parent with positive behaviours – such as eye-contact, hugging and affection. While these children can be comforted to some extent by other people in the absence of a caregiver, they clearly prefer parental attention. Parents of securely attached children tend to spend more time and play with their children. They react more quickly to their children's needs and are more emotionally responsive than parents of anxiously attached children. Securely attached children grow up to be more empathic, caring, sharing, and mature in adulthood than children with anxious attachment styles. Mothers who respond inconsistently or who interfere with the child's independence and private activities produce infants who explore less, cry more, and feel anxious. Mothers who consistently reject or ignore their infant's needs, produce children who are likely to avoid contact. securely attached adults find it easier to become emotionally close to others and feel secure in intimate relationships, but do not create relationships of co-dependency. They tend not to worry about being alone or rejected; having a higher degree of self-acceptance. this style of attachment develops through warm and responsive interactions with their partners. People who are securely attached tend to invest in more positive views of themselves and their partners. They also hold positive views of their relationships. They are likely to experience a sense of fulfilment and adjust to changes in their relationships. securely attached adults feel relaxed being close to or separate from their partners. Many seek to balance intimacy and independence in their relationships. They experience trusting, long-term relationships - with higher self-esteem and a tendency to express their feelings, even vulnerability. As parents, they are more emotionally available and responsive to their child’s needs, as well as capable of regulating positive and negative emotions. They seek support but do not allow themselves to become dependent.

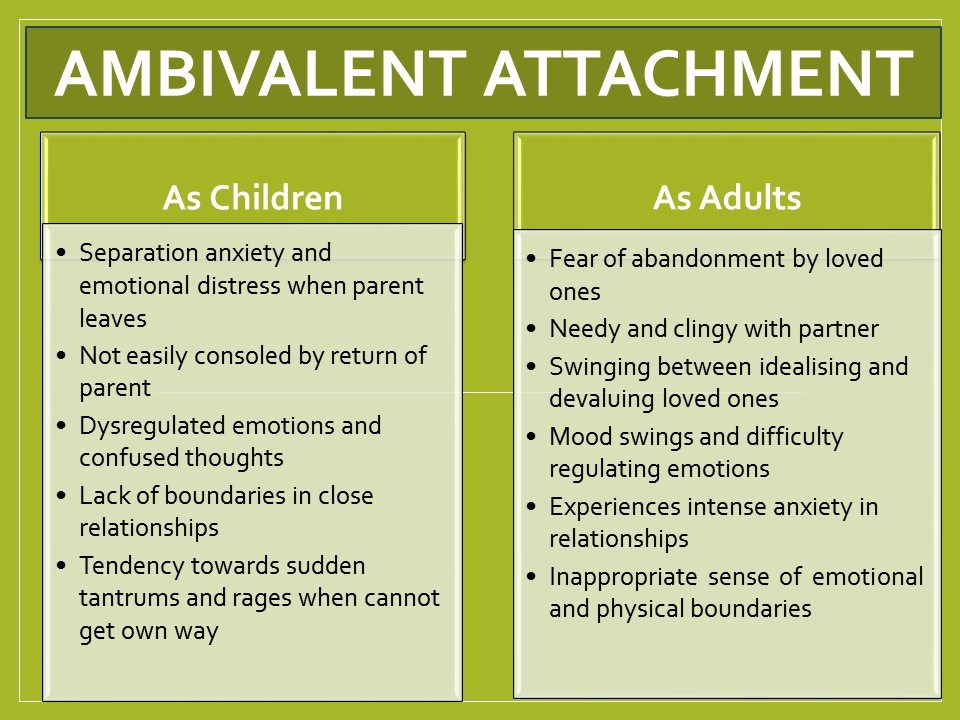

Ambivalent Attachment – ambivalently attached children may feel anxiety in relationships, having an unresolved attitude towards closeness and intimacy. This may be expressed as a sense of ‘push and pull’ in relationships, veering between emotional neediness or pushing away from parents. Children may also alternate between idealising and devaluing parents, depending on whether they respond immediately to a child’s needs or not. they may feel extremely suspicious of strangers. Such children display considerable distress when separated from their caregivers, but do not seem reassured on their return. in some cases, the child can passively reject the parent by refusing comfort or an angry outburst. As these children grow older people often sense them as being clingy and over-dependent. Adults with an ambivalent attachment style lack trust and feel reluctant about becoming close to others. They often assume their partner will not reciprocate their feelings or abandon them. this leads to frequent conflicts and breakups, because they perceive their partners as cold and distant, when they merely wish to take space and time alone. They may become intrusive and controlling with partners, even showing jealousy of sharing their partners. Ambivalent adults feel especially distraught after the end of a relationship, becoming preoccupied with abandonment and immersing themselves in emotional intimacy too quickly with new partners. their partners may experience them as emotionally intrusive and chaotic; as they seek high levels of dependency, approval, and responsiveness from their partners - a condition colloquially termed as clinginess. They often doubt their worth as a partner and blame themselves for their partners' lack of emotional responsiveness, feeling they are repulsive or deserve rejection. This leads to less confidence and self-esteem, as they push loved ones away by exhibiting intense levels of expressiveness, anxiety and impulsiveness in relationships.

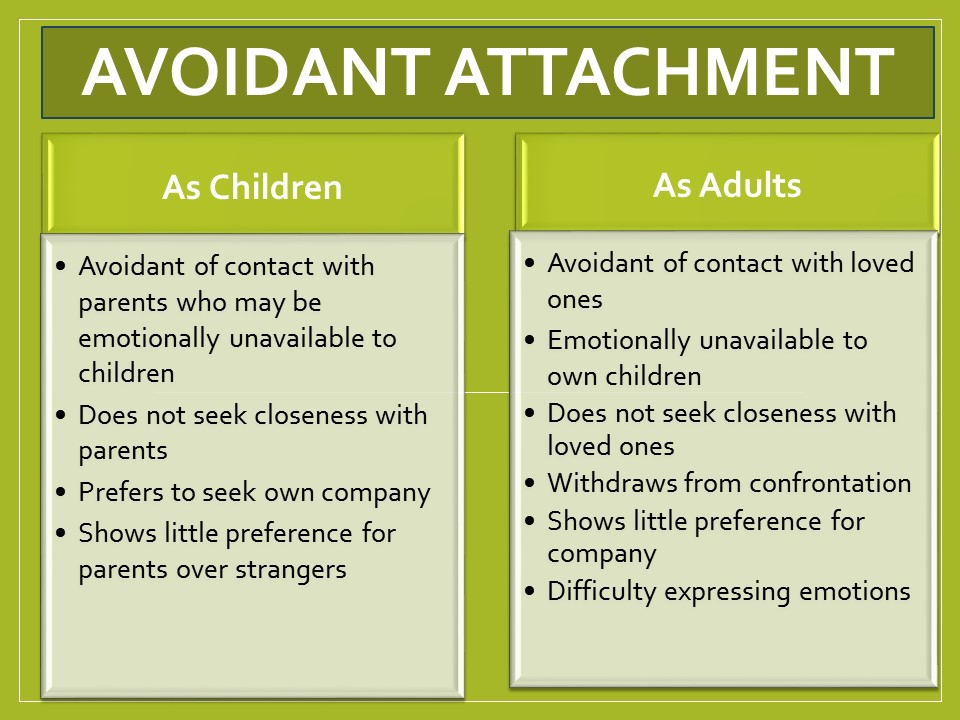

Avoidant Attachment - children who have avoidant attachment styles tend to withdraw from intimacy or closeness with their caregivers. This becomes pronounced after a period of neglect or absence by the caregiver. some children may not openly reject attention or care, but neither do they seek out contact. Children with an avoidant attachment style show little preference between parents or strangers. They may become preoccupied with their own company and privacy; withdrawing from interaction with others and ownership over their possessions. avoidant adults tend to feel independent and self-sufficient, preferring not to depend on others or having others depend on them. They may desire a high level of isolation or long periods of withdrawal, avoiding intimacy altogether. They view themselves as being untouched by feelings of closeness and often deny needing intimacy with partners whom they view as clingy, over-emotional and weaker than themselves. Avoidant adults have difficulty expressing their feelings, they are emotionally withholding and do not invest much value in relationships; experiencing little distress when a relationship ends. They often make using excuses, fixate on their own interests or avoid intimacy during sex. As such they may fail to support partners during distress and find it problematic to share their own feelings, thoughts and affections.

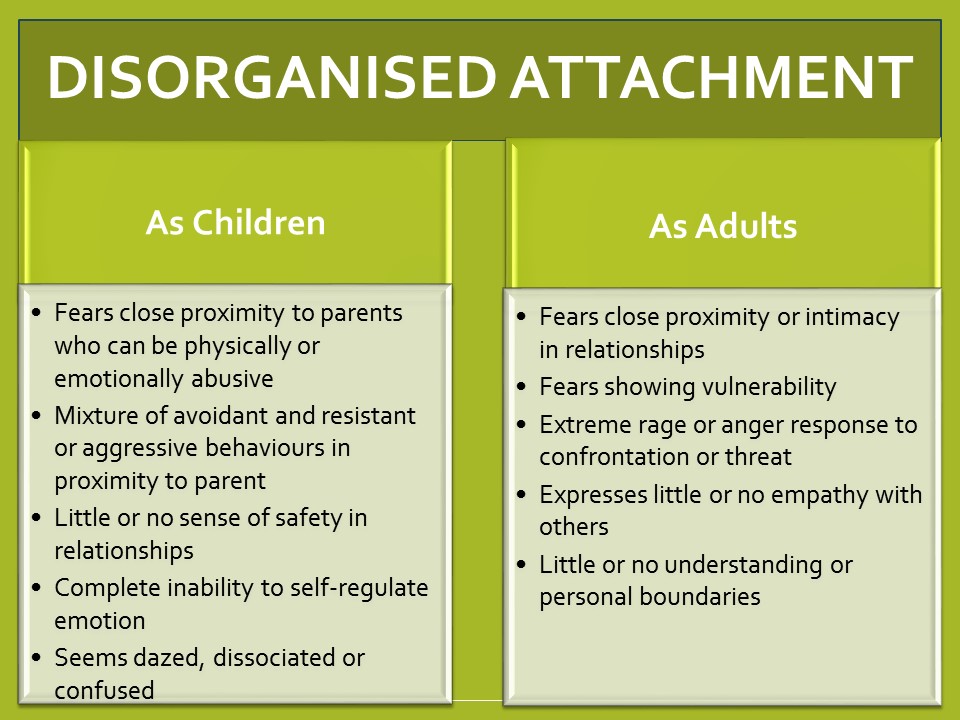

Disorganised Attachment - children with a disorganized attachment style show a total lack of trust in any attachment. they may have a pathological fear of intimacy and find themselves lacking in empathy. Their actions and responses to caregivers are often chaotic, aggressive and include a mix of avoidance and resistance. Disorganised children may display detached, cruel and dissociative behaviours - sometimes seeming angry, confused or apprehensive in the presence of a caregiver. They may be in a constant state of arousal and anxiety, expecting abuse or neglect from a caregiver. Parents of these children act as figures of terror, chaos and extreme emotional absence. Adults who have experienced traumatic losses (such as the death of a parent) or sexual abuse in childhood often develop this type of attachment and fail to forge close or long-term relationships with others. They may unconsciously desire emotionally close relationships, but find it difficult to trust others or depend on them. Such adults, believe they will become weak and easily hurt if they get too close to others. On the one hand, they may seek out people who will nurture and provide for them; however, they may also experience difficulty with emotional closeness. this chaotic blend of intensely conflicted feelings may lead to paranoia and highly negative perceptions about themselves and their partners. They commonly view themselves as unworthy and do not trust the intentions of their partners, suspecting they may harbour ulterior motives. disorganised adults frequently protect themselves, by suppressing their emotional needs. They may self-sufficiency and become neglectful or violent as parents. While in adult relationships they may fear being overwhelmed, judged or rejected.

When you attend appointments couples counselling twickenham we will discuss your attachment patterns and address how they impact on your relationships