Reward & Punishment

Breaking Cycles of Anxiety

HOW TO BREAK OLD CYCLES OF ANXIETY AND AVOIDANCE:

Despite what you may think, human motivation is driven much more by instinct and unconscious impulse, than by any rational thought process or higher moral imperative. The brain is wired up for survival first, and survive it will, at all costs. If it feels under threat or in need it will respond accordingly with our without our conscious agreement.

Most of us are aware, for example, how easily feelings of hunger, fear, anger and desire can override any higher sense of purpose or reason. So under stressful conditions, it is not surprising that we are conditioned to respond to heightened sensory stimuli and act fast. The brain focusses in on its absolute needs, primes itself for action and prioritises all of its instincts in achieving that goal. It therefore processes perceptions and emotional responses much quicker than our higher though processes when there is a critical decision to be made. And focuses on goal-oriented behaviour even in our interactions with others – such as disarming or placating an opponent, beating a competitor, winning an argument or avoiding conflict.

When we are anxious or fearful, there is very little time for rational thought at the critical moment when action is taken. It is far too slow to process. If we feel under threat the amygdala in the brain bypasses the hippocampus and higher cortical regions in favour of the primitive brainstem as the fight and flight response kicks in.

This is because all living organisms are predisposed towards survival. So our physiological sensations and emotions send much stronger neurochemical signals to override conscious thought in favour of our instincts so we can take quick and decisive action earlier. It also explains why our beliefs, values and moral codes are so often disregarded in the face of adversity when base emotions such as fear, hunger, sexual appetite and desire are more effective at motivating us. It is also who it is futile for us to think ourselves rationally out of breaking a bad habit. We simply need to learn a new habit which brings a greater sense of reward than satisfying our impulses with immediate gratification.

It is the way our brain has been predetermined from birth by our genetic encoding, as well as the way our brains have been hard-wired by biology and evolution to respond to primal instincts first. Even when we think we are responding to high moral standards, (when we refuse to be seduced by a sexual liaison, or give into our prejudices against those more vulnerable than ourselves) we are more likely to be responding to fear of being exposed and shamed, rather than our moral integrity.

When we look at how the brain functions by measuring its neurological activity through an EEG (electroencephalogram) we can observe that the primary regions of brain activity occur in the perceptual lobes, the limbic region (emotional centre) and the sensory-motor cortex in response to external stimuli. Such studies show that all external stimuli that are perceived by our five senses are filtered first through the relay circuits of the thalamus, hypothalamus, amygdala and hippocampus (in the limbic region), long before they reach the higher cortical regions of the brain reserved for conscious thought and rational cognitive processes.

If human behaviour is triggered by reflexive processes in the body and brain, then it is because unconscious impulses and urges are sending far stronger neural signals for us to act upon. And although it may be an uncomfortable truth, very few of our actions or learned patterns of behaviour are responding to rational thought – which is why it is so hard to break an old habit, or an addiction, or any form compulsive behaviour by willpower alone. Even when we know it’s harmful for us to act on impulse.

Although thoughts and cognitions do influence human behaviour, they are often directing our behaviour from a distance. In other words, our thoughts and ideas may inform our behaviour long before events, or sometime afterwards but only when we have enough time to pre-plan or reflect events (when we are somewhat removed from them. Even then predetermined decisions are made as a result of an interaction between our emotions and thought processes, in order to motivate future action.

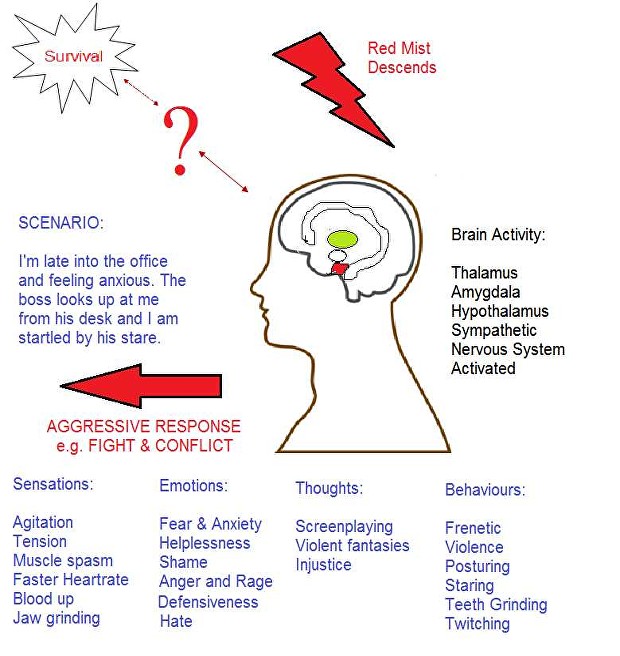

In this scenario, the client feels highly anxious after reaching work late and reacts with an aggressive/angry response which is disproportionate to the level of threat or adversity he faces. Anticipating some kind of confrontation he prepares to justify himself to an authority figure, which appears to remind him of a past experience of being shamed. This provokes a ‘fight response’, as the body tenses the posture primes itself for conflict. This escalates the level of stress to a state of hyperarousal which feels unmanageable for the client and can only be discharged after an aggressive interaction with someone else. Expressing anger or acting out with using aggressive behaviours is possible, even likely.

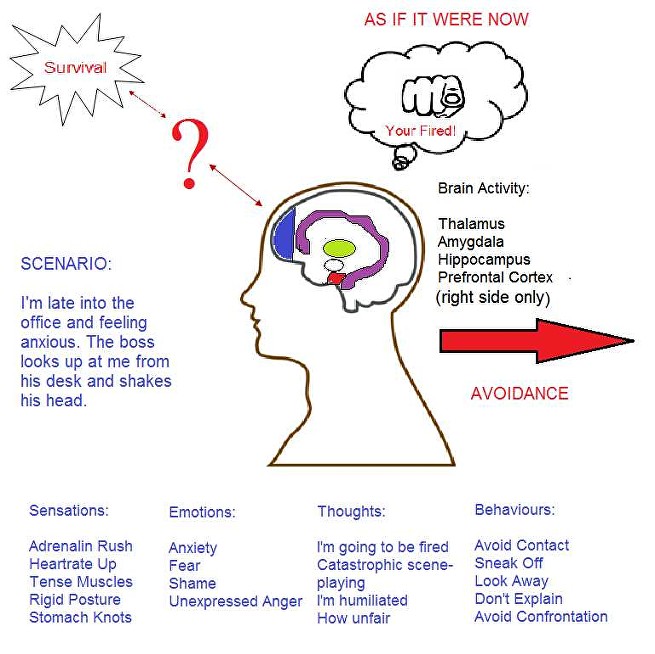

In this scenario, the client feels a heightened sense of anxiety after reaching work late and reacts with an avoidant response which is disproportionate to the level of threat or adversity he faces. Anticipating some kind of confrontation he takes evasive action, as if he were experiencing a real and present danger in the present moment. This provokes a ‘flight response’, as the body tenses prepares to flee from danger. This escalates stress levels to a state of hyperarousal which feels overwhelming for the client and can only be discharged after avoiding any kind of conflict. Unexpressed anger, preoccupation and withdrawal lead to a cycle of avoidant behaviour and even clinical depression or generalised anxiety disorder are possible.

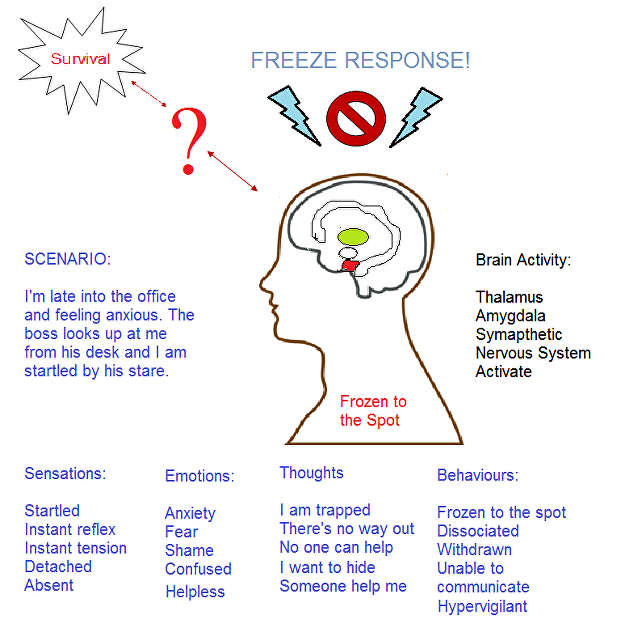

In this scenario, the client feels a heightened sense of fear/panic after reaching work late which is disproportionate to the level of threat or adversity he faces and reacts with passive response, unable to activate his ‘fight or flight response’. Experiencing a sense of immediate danger this provokes a ‘freeze response’, as the body tenses and prepares shut down. This level of stress to a state of hypo-arousal (under-arousal), which feels overwhelming for the client and cannot be discharged. Unexpressed fear and anger is internalised, along with paralysing shame and leads to a cycle of restricted motility and dissociative states, even traumatic symptoms, panic attacks or and PTSD are possible.

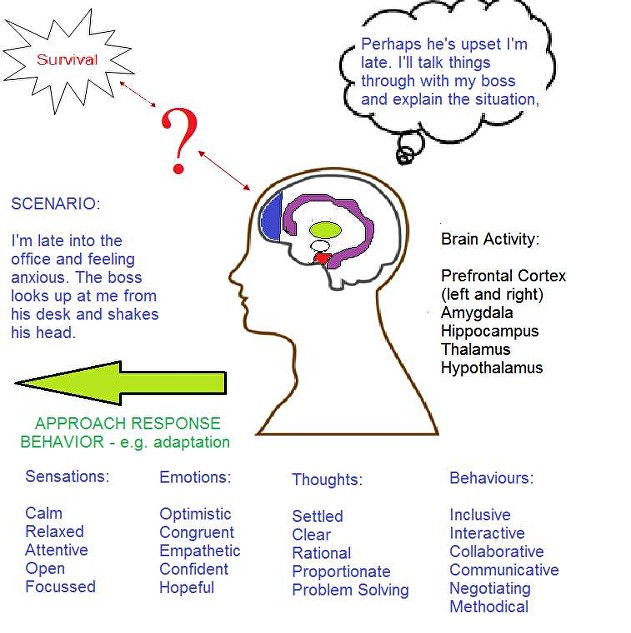

In this scenario, the client feels a moderate level of arousal after reaching work late and reacts calmly and reasonably which is proportionate to the level of difficulty he faces. Anticipating some kind of interaction with his boss he prepares to explain his reasons for being late, which appears to remind him of a. This provokes an ‘assertive response’, as which involves being confident enough to resolve any issues through asserting his own position, whilst taking the requirements of his boss into account. This diminishes the level of stress to a state of composed confidence for the client and is easily discharged by communicating calmly. Expressing himself, resolving any issues and coming to a mutually satisfying agreement between him and his boss is likely. This is more likely to lead to approach behaviours, problem-solving and conflict resolution in future.