Co-Dependency In Relationships

At Couples Counselling Whitton, I try to help couples break the trap of co-dependency. Co-dependency is a type of relationship in which both people fulfil mutually dependent roles. This is where each person in the relationship comes to depend heavily on the role of the other to feel satisfied. For example, if one person is ill, addicted or depressed, they may depend on another person’s role as the carer, enabler or rescuer. While the rescuer feels needed and wanted by the one who is vulnerable, the other is unable to take care of themselves. This is typical where couples come together in a whirlwind romance and strongly identify with each other's needs and feel as if the other person has completed them. At first the couple idealise each other as they discover very strong feelings they share in common. But after a while the cracks may begin to show. Perhaps one person is unable to match the intensity or needs of the other. One or both people may fear being alone and begin to smother the ohter person. They may feel clingy or controlling, as if there is no air to breathe. One person may begin to become more distant or feel unable to meet the needs and demands of the other person. All the boundaries begin to disappear and each person slowly loses their own sense of identity.

The Nature of Co-Dependency

When person feels incomplete, helpless or have a weak sense of Self they may come to rely on others to fulfil their needs. Rather than being themselves they end up playing a role - rescuer, helper, carer. For a while these roles are seen as loving, caring and devoted. And there are genuine feelings of love and affection present; as well as a strong sense of identification with each other – perhaps because of a shared history of trauma. There may even be a high degree of empathy and compassion at first, but the boundaries quickly become blurred as each person becomes lost in their role. In this co-dependent relationship one person may help the other get their life on track by overcoming a personal crisis – e.g. such as a tragedy, addiction, illness or trauma. However, both parties are expecting a return on their investment at some point in the future and when it doesn’t come, it can lead to a great deal of disappointment and resentment. This is why mutually dependent roles remain fixed, because they cannot be changed without upsetting the natural order of the relationship. This is because these roles have conditions attached to them and when they are not met, each person uses their power to influence the other person into re-enacting the role again and again. It can also lead to each person feeling let down, disappointed or angry when the roles and demands are not being met. This is where emotional control is being presented as love and devotion, but feels like a trap. As each person's independence and separate identities begin to disappear they become lost and enmeshed in each other.

No villains or monsters here

This does not make either person a monster or a victim. It does not make them devious or consciously manipulative. It means they are often acting out of anxiety – e.g. a fear of being rejected or abandoned. Besides, most people fulfil these roles unconsciously, while feeling genuine love for each other. However, due to the negative impact of a previous relationship or experiences in childhood, they feel an unconscious impulse to work through the unfinished business of the past in their present relationship. Simplistically speaking for example, a man whose mother died when he was a child might seek out a very maternal caring woman; or woman whose boyfriend was abusive may seek out a man who is passive in temperament.

What’s wrong with these roles?

The role of rescuer may serve the self-interests of one person at the expense of the other – but is presented as an act of caring and loyalty. This means that one person relies on a loved one to find approval and validate their self-worth, while the other enjoys the influence of being needed. The strength of the bond relies on a mutual belief that each person was predestined to meet and fall in love, while in reality it is characterised by a need to manoeuvre one person into fulfilling the self-needs of the other. It may feel like unconditional love, but it is in fact predicated on a desperate sense of helplessness.

The features of co-dependency

A lack of boundaries - when we lose our boundaries it is because we find it impossible to believe that others cannot think and feel like us. We’re so accustomed to believing others are irrational or unreasonable if they do not share the same version of the truth. We may share our feelings without inhibition and ask for reassurance but this is a form of control as we dump our emotions on our partners and expect them to fix us. When we do not resolve our own issues, we assume that our partners will do it for us. We need to be constantly comforted or we end up feeling anger and resentment. It also means we get caught up in each other’s drama and entangled in each other’s problems.

So you feel ‘you can’t live without them’ - this may sound like a declaration of unconditional love, but it isn’t. It’s a trap. Idealising a loved one to this extent may seem like devotion, but it can demonstrate desperation and fear of abandonment. Not allowing yourself to be independent, can lead to feelings of being smothered or confined. Living in each other’s pockets means you become entangled in each other’s problems. ‘Emotional dumping’ becomes a substitute for sharing one’s feelings. The closer you push, the more overbearing it feels. Too much closeness creates dependency and learned helplessness as you expect others to solve your problem. You take each other for granted, making unreasonable demands and resenting each other. Real intimacy, thrives when you strike a balance between being separate, as well as close. Independence, offers each individual the space and time for personal fulfilment and growth. It allows people to develop their own interests and pursuits that reinvigorate the relationship. Spending time apart can also rekindle desire.

Control in the name of love – if we feel the need to control someone, it is not love but fear. We might feel betrayed by their independence or fear abandonment, so we seek to influence their behaviour. And justify this as an act of love. Jealousy is a good example because we want our partner to comply with our will and become our possession. We may offer love in return, but it comes with conditions attached. In order for you to feel loved and validated, you create the expectation: they must be who you need them to be. But this comes at a cost - it doesn't allow the other person to be who they truly are. Instead, they have to comply with who you want them to be.

‘Prove it to me’ – in some relationships couples depend on proving how much the other person loves them. These proofs may be demanded through endless persuasion and emotional blackmail. The proofs asked for might be in the form of grand gestures like expensive gifts or personal sacrifice that seem to demonstrate to the recipient how much their partner loves them. If this is a repetitive cycle it is because one person is using the situation to exploit the other, while the other is complicit in allowing themselves to be manipulated.

Safety whatever the cost – couples can be afraid of confronting each other with the truth and will do anything to avoid it, keeping back their emotions for fear of conflict or displeasing the other. This leads to pent up frustration, as arguments are swept under the carpet in order to keep the peace. But anger begins simmering away until each person is fit to explode. It may feel like stepping on eggshells, while not remaining true to themselves.

Fixed and rigid roles

Couples often find themselves falling into rigid patterns of relating with roles they cannot seem to get out of. Perhaps they feel they must behave in a particular way or carry out certain duties. At first each person plays to their strengths and seems to complement each other, but very soon the roles become restrictive and unbearable. The couple begin to compete for status and validation, or refuse to learn new roles for fear of losing control. An example of this are arguments around how couples divide up the responsibilities for up paid employment, housework, childcare and finances.

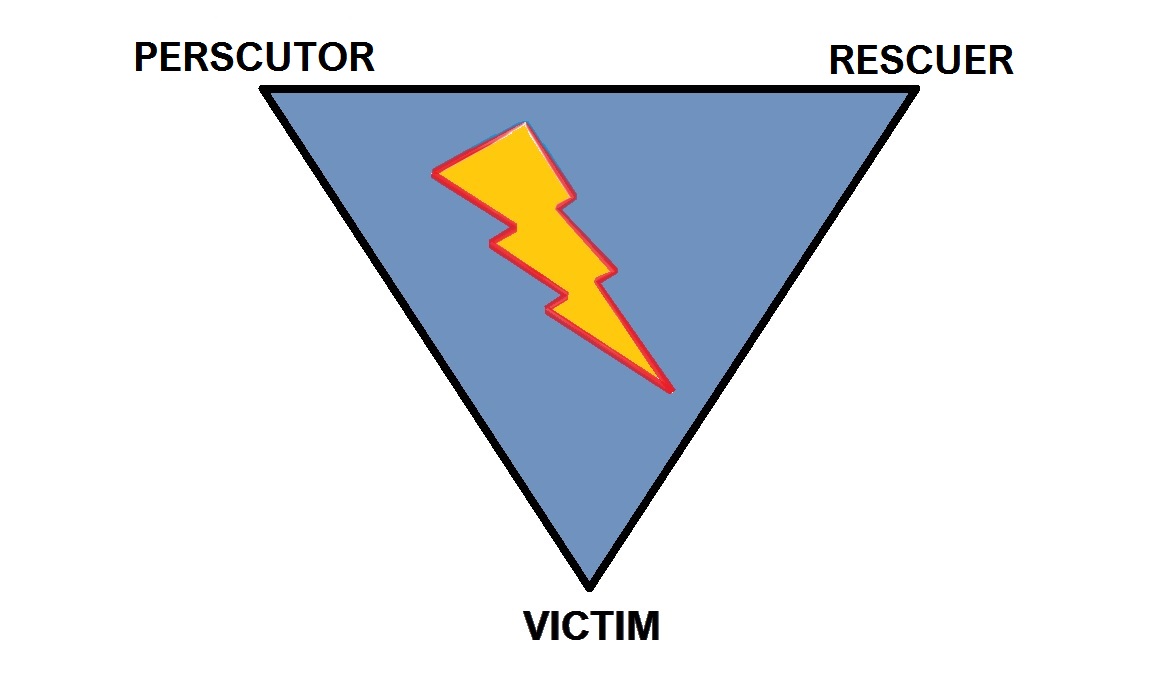

The drama triangle - is a psychological game played out by couples who are trapped in a compulsive cycle. This is where one person assumes the role of victim and invites the other to rescue them, using vulnerability as a way of receiving support and reassurance. This lures the rescuer in, who feels needed and idealised by the ‘victim’. At first, both individuals feel loved and validated, but after a while the cycle becomes so ingrained no one is willing to break it. Both people may start to feel controlled and smothered, because they’re not willing to step outside of the roles they created. This is when the rescuer turns persecutor, because they’re perceived as controlling or cannot live up to expectations, keeping back the victim from growth and independence. Finally, the persecutor feels demonised by the person he was attempting to rescue. As such, the persecutor turns victim and the victim turns rescuer – to save their feelings and prevent themselves being abandoned. And so the cycle continues.

My soul mate – this is often used to describe someone who is your perfect match – ‘the one’. It is often someone you identify with closely, who shares a similar history or qualities as you. Often, however, a soul mate becomes someone with whom you lack individual boundaries. As if you cannot feel complete without the other person. At first it feels like your soul mate is the only person in the world who can understand you or take care of your needs. But it isn’t healthy and quickly becomes restrictive. To remain on a pedestal the idealised partner must not display feelings or behaviours that contradict the ideal. They also need to be constantly validated by the person who idealises them. The soul mate believes they cannot give-up the role of perfect partner in case they are abandoned or because they might be demonised and devalued.

Being the good caregiver - a healthy relationship exists between two adults of equal standing, not one parent and a child. When we’re mothering or taking care of someone who is not caring for themselves, it’s frustrating and disempowering for both parties. As we learn to take care of our own needs, we become more independent. When someone else is fixing us all we learn to feel is helpless. A parent/child relationship is unappealing and lacks desire.

At Couples Counselling Twickenham, Whitton, we will discuss potential patterns of co-dependency in your relationship and address them so that you can establish more healthy boundaries and develop separate identities again.